International Women’s Day (8 March) has dawned on us once again. Regardless of ethnicity, most of us Malaysian women will not think much of the occasion as we collectively ease into the busy period that is post-CNY. At best, International Women’s Day punctuates our busy lives in the form of commercial advertisements, seizing upon the message of the day which is ‘You Deserve Better Rights‘ and turning it into ‘You Deserve Better Things‘. This is a simple but effective marketing strategy.

Jokes aside, anyone with a passing knowledge of the women’s rights movement will appreciate the importance of International Women’s Day. It is a reminder of how far we have come. Despite this, we have not yet achieved gender parity. Sexism/gender discrimination is a universal phenomenon.

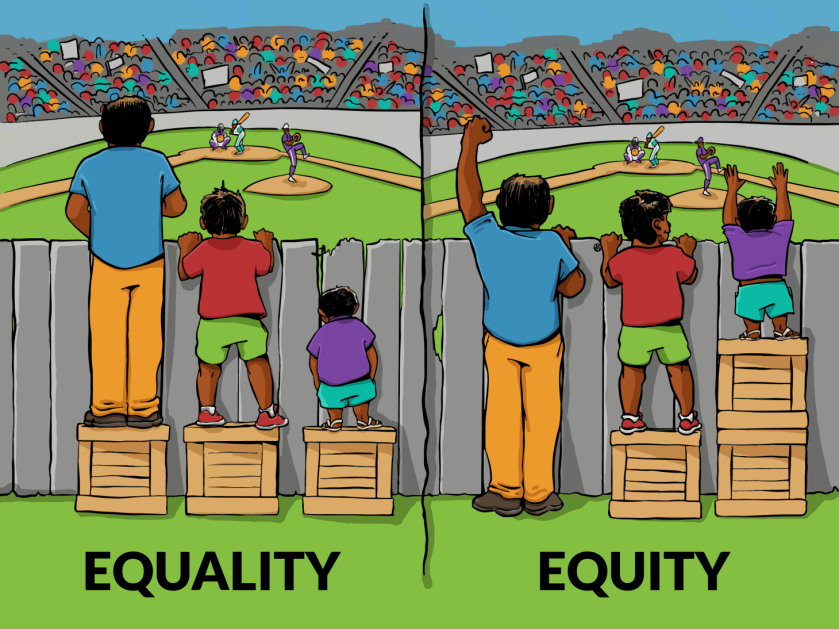

In lieu of the occasion, I wanted to pose the following question to readers of this blog: Does ‘equality under the law’ help or harm women? Some of you must be thinking, ‘of course equality under the law helps women, don’t they want equality?’ Not so fast. If everybody had the same interpretation of the term ‘equality’, there would only be disagreements over whether women deserve equality or not. However, even among proponents of equality there may be disagreement over what equality should be. There is a narrower definition called formal equality and a broader definition called substantive equality.

Formal equality (“Equality”)

For ease of understanding, formal equality is depicted in as ‘Equality’ in the above illustration. This model provides that all individuals, regardless of gender, sex, race, class, etc. will be treated alike under the law. For example, individuals are governed by the same laws of contract regardless of their background. As an illustration, imagine being a pisang goreng vendor in Klang. You are a rich man. You enter into an oral agreement with a customer but they refuse to pay up and also dispute the terms of the agreement. The chances of winning a civil suit against this person depends on how the courts construe your agreement in light of the existing legal principles. The same legal principles would apply even if you were a poor woman. Seems fair, right?

Yet, because you are a rich person, you are able to sustain the legal suit for a longer period than you would have if you were poor. Since the agreement was not written, the court must decide on the balance of probabilities whose evidence is more compelling, so if the judge is sexist, you stand a better chance convincing the court as a man than a woman. Although the laws apply equally to all, the outcome differs when certain variables are tweaked, despite the merits of your case.

Substantive equality (“Equity”)

Substantive equality accounts for the wider social context and mainly concerns itself with equality of access/opportunity. The law is then modelled with the disadvantaged in mind. For example, substantive equality may be done where legal aid is automatically given to those earning below a certain level of income or 90-days maternity leave is made mandatory within the judicial service to encourage gender diversity. With those policies/laws in place, an environment is created so as to give even the ‘poor woman’ version of your pisang goreng story a shot at winning your case fair and square.

Some critics of substantive equality say that it generates inequality. They would say that men are disadvantaged because women benefit from statutorily mandated 60 days maternity leave, while men have no similar mandated law. However, it must be remembered that women are the ones recovering from pregnancy and are expected to bear the brunt of motherhood. Women are looked down upon if they shift the burden to their male partners and decide to take some time off for themselves. Another common criticism is that it fosters dependency and a victimhood mentality. This is a fair concern, as the purpose of substantive equality is to enable the disadvantaged to feel in control and in power, even when the reality appears otherwise. (P.S. The author is totally in favour of more paternity leave!)

Conclusion

In my humble opinion, substantive equality is formal equality with fries and coke on the side. In other words, it allows the creation of laws and rules with richer content and safeguards the interests of the community at large. After all, no one is an island and the more opportunities are given to people who need it the most, the healthier and happier society becomes. None of us had a choice in what families to be born in, what gender we would be assigned, nor what ethnicity we would inherit. Half of the world’s population didn’t get a choice to be born and assigned the so-called ‘weaker’ sex. Give us the equal opportunities, education and equip us with confidence. There is a lot of potential to be unleashed in each and every one of us, regardless of gender and sex.